At one point in The Right to Sex, a collection of essays in feminist theory, the philosopher Amia Srinivasan writes that women “have never been free.” The problem she circles around from the opening pages is what it might take to liberate women from all forms of subordination. Her book is an attempt to think toward that ideal: “let us try and see.”

The result is an inviting, accessible, and powerful read. As I moved through the work, I felt as if Srinivasan was situating me on a map so I could proceed more effectively and intelligently as an advocate for all women. I shared this with her one day this summer over Zoom. “Yes, I’m not trying to give answers,” she told me, “but help people get a better sense of the possibility space, the conceptual and political terrain.”

Part of this orientation involves identifying some of feminism’s hazards. The sexual revolution, she writes, did not give women more freedom so much as lead to the ubiquity of unequal sex between men and women. Liberal feminism focused mostly on women’s choice and consent, which led, paradoxically, to the preservation of hierarchies of power, including those based on race and class. Srinivasan argues that progress requires us to acknowledge how our desires are profoundly shaped by political forces in an unfair world, to notice “what forces lie behind a woman’s yes.” She insists that feminists look to the most powerless for direction: women of color in racially and economically stratified countries, who tend to be poor. Only then can women as a class begin to approach liberation.

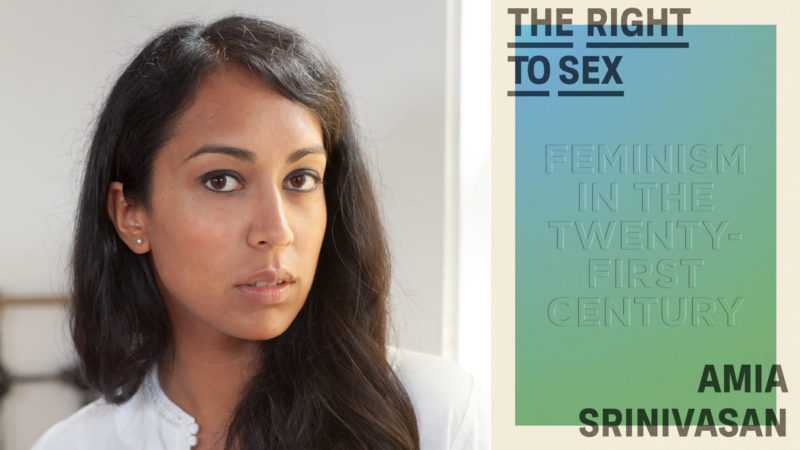

Few living philosophers have had the same reach outside the academy as Srinivasan, who has written for the London Review of Books, The New Yorker, and the New York Times about topics as wide ranging as animal consciousness, surfing, sex, and suicide. Born in Bahrain and raised in Taiwan, New Jersey, New York, Singapore, and London, she received her BA from Yale and her PhD in philosophy from Oxford, where she says she was rarely taught by a woman. “Feminist theory wasn’t part of my formal academic program,” she told me. “In fact, I’ve never been taught a feminist text.” Srinivasan came to feminist literature on her own in graduate school, through informal reading groups with friends on Judith Butler and Catharine MacKinnon. Soon she became convinced that feminism was “the correct orientation to have to the world.” Now the Chichele Professor of Social and Political Theory at the University of Oxford, she regularly teaches feminist thought, and many of the essays in her book were formed against the backdrop of discussions she’s had with her students: “You can see the theme of teaching my students as a leitmotif through the book.”

Over the course of an hour, during which we were periodically interrupted by my neighbor in New York taking a chainsaw to a tree, we spoke about why the language of consent hasn’t liberated women, the problems of the Me Too movement, and why seeking justice through social media or carceral systems isn’t necessarily in line with feminist ideals.

Although her book is a work of feminist theory, during our conversation Srinivasan was keen to point to the limited role theory plays in women’s liberation. “Sometimes people say that you’re a feminist insofar as you believe that women are or should be equal to men. I think that’s setting the bar way too low for feminism,” she told me. “It’s also failing to understand what feminism is: a political practice, not just a set of ideas. When feminist theory loses its way, it’s very often because it disassociates itself from the living breathing thing that is a radical feminist political practice. We should be talking about feminisms in the plural as a set of existing social and political movements with long, rich, and complex histories. Feminism is something that happens on the street. It happens in factories. It’s a struggle.”

—Regan Penaluna for Guernica

Guernica: Where did the idea for the book come from?

Srinivasan: The positive response to my essay “The Right To Sex” in the London Review of Books made me think that there was a broader appetite for the kind of thing I was trying to do, which was speak about feminist issues in a way that was broadly accessible while taking them on in their full complexity and ambivalence. When I sat down to think about it, I realized that I had a set of particular interests in feminism that were all united by this broader theme of thinking of sex as a political phenomenon.

Guernica: You argue that we need to take a more nuanced approach to consent as a means to women’s liberation. Why?

Srinivasan: I think consent has an important role to play in any conversation about sexual injustice, and consent training is all to the good. But consent is also a very blunt tool. Sexual consent involves a ritual performance of either verbal or nonverbal agreement; it pictures sex as a form of transaction or negotiation. The contractual model points to something pathological about how we sexually relate to each other. Think about any kind of standard contract: one person wants something that the other person might not want to give, and so that’s why you need this formal agreement. Each party comes to the negotiation trying to max out the satisfaction of their own preferences. But what if young men weren’t socialized to want sex with women and girls who don’t want to have sex — what if that weren’t a turn-on?

So, it’s not that I think we should drop consent entirely. But we can learn from other ways we relate to each other where we don’t have consent practices. For example, think about the way you relate to your best friend when they are grieving. You don’t ask for consent before comforting them, and it doesn’t mean you have permission to do whatever you want. Constitutive of real friendship is a kind of sensitivity to the needs and wants and identity of the other person. Now what would it be like to cultivate a similar kind of ethics in sex?

That said, I think we should be very cautious of pathologizing forms of sex that don’t conform to the bourgeois ideal of loving, mutual, monogamous sex. It’s not only unrealistic, but problematic to think that all sexual interaction must be analogous to what you do with your friends, because there’s got to be room for anonymous sex, promiscuous sex and regretted drunk hookups. I don’t think everyone has to engage in that, but we certainly want a world in which people are permitted to engage in that. I think there’s a kind of difficult balance to be found here between not being puritanical and allowing a range of sexual expression, but also acknowledging there’s a lot that’s quite pathological about the way that we sexually interact with each other, especially across gender lines.

More mundanely, there are lots of cases familiar to us where people, usually women, consent to sex, but where that sex nonetheless seems problematic on its face. To offer one example: I think many (though certainly not all) sexual relationships between professors and students are consensual, even according to a stronger, “affirmative consent” standard. And yet they are intuitively — and, in my view, actually — problematic. But the reason, I think, isn’t because women students don’t or can’t consent.

Guernica: I found your essay “On Not Sleeping With Your Students,” fascinating. Your discussion of its overall wrongness doesn’t hinge on a failure of the student to consent to sex with their professor (though in some cases, you acknowledge that this is the case), or on a critique of the professor’s sexual desire to sleep with a student. Rather, you write that the problem lies here: “When the teacher takes the student’s longing for epistemic power, and transposes it into a sexual key, allowing himself to be, or worse, making himself the object of her desire, he has failed her as a teacher.” When I read that, I wondered why more people aren’t talking about the issue from this angle?

Srinivasan: There’s partly a historical reason for this. Most of the regulation on teacher-student sex in the university context has happened in the US. There, sex on campus is generally treated under the heading of sexual harassment, which has been legally tied to the notion of either nonconsensualness or unwantedness. Those working within the consent paradigm who sense a problem with teacher-student sex understandably reach for a consent-based explanation: the difference in power between professor and student, they say, makes it impossible for a student to consent.

I think this notion is problematic. It infantilizes women students, which a lot of feminists said when these regulations first started appearing in like the 1980s and 1990s in the US. It’s also just descriptively implausible. Sure, there are cases where professors use their coercive powers to get sex from their women students. But there are lots of cases — I mean, academia is full of professors married to their former students — of young women who love and consent to relationships with their professors. I don’t think anything is gained by denying consent here.

Once we acknowledge that you can consent to sex and that there still might be something problematic at work, then you can see the actual phenomenon clearly: in cases of genuinely consensual professor-student sex, there is still a pedagogical failure. There is an implicit agreement as part of the practice of what it is to teach, and what it is to learn, and to be in a university setting, that is being undermined when a professor sleeps with his student.

Guernica: It was interesting how you turned to Freud to underscore the ethical obligations a professor has to their students.

Srinivasan: Many people who want to defend professors sleeping with their students will invoke the Freudian notion of transference, which is the tendency of the analysand to develop intense feelings of love and infatuation for the therapist. But this is to crucially miss Freud’s own warning to the analyst, which is you’ve got to actively manage transference. If you’re any good as a therapist, transference will happen. You’ve got to anticipate it and use it as a tool in the psychoanalytic setting, Freud says. I think there’s something analogous in teaching. If you’re a good teacher, and you have the right kinds of connections with your students, you’re going to arouse strong feelings in them. A good teacher expects this and turns it into something that becomes ultimately productive for the activity they’re engaging in, rather than siphoning it off and diverting it for their own ends.

Guernica: If we assume our unconscious is shaped in the psychosocial world of patriarchy, as you say, then I wonder what you think about the moral regulation of sexual desire. For example, can subordinate sex ever be morally permissible for a feminist, let alone be a feminist ideal?

Srinivasan: The phrase “feminist ideal” is interesting here. Are you asking, would such sex take place in the feminist utopia where we have dissolved not just patriarchy, but gender? Would people still want to be subordinated or act out fantasies of subordination? Maybe. I think they wouldn’t want to be subordinated under the sign of gender. In the feminist utopia, you wouldn’t have one gender that’s coded as dominant, and the other one that’s coded as submissive, but you still might have some playing out of complex psychosexual dynamics.

When we’re thinking about the non-ideal world, the world in which we live, I think it’s extraordinarily dangerous to ethically legislate against people having the kind of sex that they say that they want to have so long as it is with consenting partners. There’s a long history of that notion being mobilized against LGBTQ people. I also think that the human psyche is extraordinarily complex, and we don’t necessarily know what it’s doing for any particular woman or any particular man to act out a certain kind of fantasy. And there is an important distinction between fantasy and reality. For example, some rape survivors find it salutary to fantastically participate or reenact their own subordination — what is sometimes called “consensual non-consensual sex.” Of course, people’s rights to participate in such sex (or sexual kink more generally) shouldn’t and needn’t rest on the fact that some people find it a useful way of addressing trauma. I think you need a sexual ethics that’s both feminist and also open to the complexity and the weirdness of the human unconscious.

Guernica: You discuss the Me Too movement and its limits, and how white feminism has used it to privilege white voices. Can you say more about this?

Srinivasan: Me Too was this incredibly powerful rallying cry that took its power from the fact that just about every woman has experienced some form of sexual harassment. It was this moment of mass consciousness-raising where lots of women — across race, class, nationality, and so on — who had felt that they had had a highly individual idiosyncratic personal experience, observed that almost every other woman had experienced this as well.

At the same time, there is this brutal fact that for many women — even if we just concentrate on the US in particular — being sexually harassed is not the worst thing about their lives. Consider the focus on workplace sexual harassment. For many women, the worst thing about their jobs is not that they are sexually harassed at them, but that they have to do their jobs under the table because they’re undocumented immigrants, or their work is precarious, physically unsafe, back-breaking, or doesn’t pay enough to be able to support them and their families. What makes their lives the worst work lives there are in the US are not things that all working women have in common.

So, when we focus on the things that all women have in common, it obscures what makes many women’s lives, and the worst-off women’s lives, truly miserable. It’s true that sexual harassment makes poor women’s lives bad, but it’s not the only thing. That’s why any movement like Me Too, that in large part has been premised on the idea of what all women have in common, will only serve the most privileged women.

Guernica: You write that many of the men implicated in the Me Too movement don’t deny their wrongdoing. What they do deny is that they deserve to be punished for what they did. What I find interesting is that you also wonder whether they should be punished, and if so, what form their punishment should take. You dig into punishment as problematic for feminism.

Srinivasan: The question isn’t so much whether these men deserve to be punished or not, but what forms of social sanction do we want to reflectively get behind, endorse, and put into practice? Who should make those decisions, after what processes? Instinctively, I think they should be democratic. I’m wary of heightened state power to coerce and punish. But it’s not that I think we should necessarily just take punishment off the table entirely, especially if you are thinking about punishment in this broad way.

I think it’s important to distinguish between different kinds of punishment. You can be skeptical, as I am, for example, that incarceration — especially of the kind that you see in the US, which disproportionately targets people of color and poor people — is a productive system of punishment. You can be skeptical of carceralism while still thinking that there need to be forms of punishment to have social change.

For example, restorative justice programs could be thought of as non-punitive, because they’re supposed to be an alternative to prison. Nonetheless, the perpetrator needs to sit and listen to what he has done, and he has to acknowledge it. If it goes well, it’s extremely psychically painful. You can think of that itself as a form of sort of social punishment. In one of the footnotes of the book, I talk about the Gulabi Gang in India. It started out as a group of poor, low-caste village women carrying large sticks, and acting as vigilantes, stopping men from beating their wives, going home drunk, and so on. Here you’ve got the threat of punishment, but it’s not a state-sponsored form of punishment. I’m not proposing that we generalize this particular practice, but I think it’s very interesting. There’s also the question about whether something like being publicly shamed on Twitter is a form of social punishment. My instinct is to think of all of these, conceptually, as forms of punishment.

Guernica: At the same time, you encouraged me to think more deeply about my wish to punish individual men for harms against women. For example, with the publication of the Shitty Media Men List and the public shaming that followed, I admit to feeling relief, as if some sort of justice was finally being served to men who normally got away with treating women so poorly. But you point out that justice in this form isn’t necessarily feminist in principle. Why not?

Srinivasan: For centuries men, or at least a certain class of men, have been able to use the coercive apparatus of the state and their own physical might against women. I think it’s completely understandable that, when given the opportunity, women want some of the same. It’s this terrible paradox of being a member of an oppressed class that, when empowered, you have to be better than the oppressors. And that means setting aside some of the very real satisfactions that propped up the system of oppression originally.

There is satisfaction to be had in wielding power against people, especially people who have harmed you. I’m not saying that no power can be wielded — absolutely not. But first of all, power should be democratically dispersed and distributed. And then, we need to have a critical and honest conversation about how it should be wielded.

I think what’s dangerous is when members of oppressed groups deny that they actually have power. Everything that’s been happening within the Me Too movement suggests that certain feminists have an awful lot of power. We have to have difficult and fraught conversations about what it means to wield that in a way that’s genuinely consistent with feminist principles.

Guernica: If woman is a being formed in patriarchal society, as I take you to suggest, do you think that woman is something to be overcome or transcended? Another way to say this is, can you be a woman and be free?

Srinivasan: What a great question. Maybe I’ll set that as an exam question next year. I don’t think any individual is free until we are all free. While I think it’s true that there are lots of women, cis and trans, who don’t experience their identity as a woman to be oppressive, I think nonetheless they exist under a system in which gender itself is structured hierarchically. My own instinct is that in the feminist utopia, there will be no gender, or there will be so many genders as to be fairly meaningless. I would like a totally arbitrary relation between people’s bodies and how they perform: how they dress, how they act, with whom they partner, how they choose to have families, and so on.

And there’s another philosophical question as well: in that system, do you still have women and men? Not recognizably. You could imagine us using those words “woman” and “man,” because they take on a new meaning. But I think it’s important to note that it can be a very important step towards liberation, and I think towards that utopian possibility, to allow people to insist that they are women or that they are men now. I’m thinking most obviously of trans people. When a trans person insists on being of a gender that, by many people, they are not recognized as being, this too is a blow against the gender system, which seeks above all else the security of fixed categories. It is no surprise that, the world over, the forces that most fiercely array themselves against trans people are also those forces that seek to repress and control non-trans women and other queer people. There are various forms of gender dissidence. Being a non-trans woman who works for the eradication of the gender system is one. But it can also be that attachment to gender realism, paradoxically, will be an important step towards the ultimate dismantling of gender.